The Paradox of Placebo

After almost 2 decades of clinical research in the areas of pain and Parkinson’s disease, I have come to strongly believe that the placebo effect (and it’s opposite: nocebo) are way too often underestimated and under-appreciated.

In the studies I was involved with (for pain and for Parkinson’s disease), placebo was a significant effect that we always had to plan for.

With pain, we had to prove that the therapy we were studying performed better than placebo in double-blind randomized controlled trials. Double-blind meant that (1) the investigator (doctor) had to be blind to whether the patient received treatment or placebo. This was because of the potential effects of the care-provider’s biases. And (2) the patient had to be blind to their treatment/control status because of the effect of their beliefs/anticipation. That wasn’t easy to do because the placebo effect could be pretty damn good. One of the studies I was involved with failed, despite excellent outcomes, because the control group did too well.

With Parkinson’s disease, there is a lack of dopamine in the person’s system, but the anticipation of a reward (e.g. from treatment or surgery) alone can cause a temporary boost of dopamine (which reduces their PD symptoms). So you have to make sure that the effects you’re seeing are caused by the therapy, and not just the patient’s anticipation of benefits.

To learn more about the power of placebo, I highly recommend reading/listening to research done by Fabrizio Benedetti , Department of Neuroscience, University of Turin Medical School, and National Institute of Neuroscience, Turin, Italy.

Mechanisms of Placebo and Placebo-Related Effects Across Diseases and Treatments (2008)

So I think it’s safe to say that it has been well established that if a person anticipates pain relief from something, they have an increased likelihood of experiencing a reduction in pain from it. This happens even if the therapy or dose they receive is a sham. There is substantial data showing that a similar effect exists with depression and immune responses. Add to that anecdotal stories about how a false-positive terminal diagnosis led to a patient’s demise, or a false-negative test-result led to a patient’s positive up-turn (those ones are really hard to prove). Of course no such evidence exists (I assume) around ligament healing. However we do know that what you believe will affect what you do and what you pay attention to.

I believe that where your attention goes, grows.

If I focus on the death and demise of my ACL, and the inevitability of surgery, I believe that’s the direction I will be more likely to head in. On the other hand, if I focus on the healing and recovery of my ACL, I believe I stand a better chance of bouncing back, either with a partially healed ACL, or at least with a body-mind that has adapted and learned to move on without a fully functional ACL.

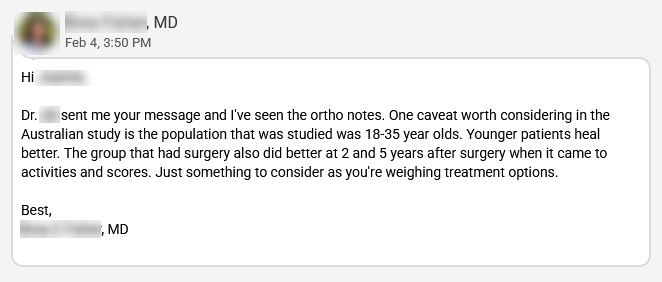

Why do I bring this up? I bring this up because of something my GP said to me last week. I told her about the research coming out of Australia about ACL healing (see article in BJSM about the Cross Bracing Protocol), sharing my clear excitement and enthusiasm for the potential for my own ACL to heal. She did not acknowledge the positive implications of this research. Instead, she responded with:

Wow, there’s a lot to unpack there.

- First talk about reinforcing (making stronger) the beliefs that with age comes less hope.

- Second, I must point out that she clearly didn’t actually read the report, because this study did include patients older than 35 (ages 10 to 58). And there’s not yet any data comparing their outcomes to ACL reconstruction surgery. There was no “surgical group” to compare to. That study starts this year. It’s a reminder that we see/hear/read what we want to. I’ll be first to admit that I want to believe my ACL could heal. That’s what I’m biased towards hearing. She wants to believe that the conventional route of surgery is the more sensible path.

- Is she not aware of the research on placebo effects? Why would you want to take steps to de-power these effects?

We know, in evidence-based-medicine, that the beliefs of the patient and of the clinician have significant effects on outcomes. That’s the paradox. We do want evidence to backup our medical interventions, and yet the evidence shows that what we believe can alter the very effects we’re trying to study.

As long as we “do no harm” in the process, what’s wrong with erring on the side of optimism? 🤷♀️

References

The fascinating story of placebos – and why doctors should use them more often

- post from The Conversation, “a nonprofit, independent news organization dedicated to unlocking the knowledge of experts for the public good.”

- A review of over 50 placebo-controlled surgery trials found that placebo surgery was as good as the real surgery in more than half the trials

- The main mechanisms by which placebos are believed to work are expectancy and conditioning.

In research studies and in real life, placebos have a powerful healing effect on the body and mind

- Also from The Conversation.

- scientists define placebo effects as the positive outcomes that cannot be scientifically explained by the physical effects of the treatment.

Mechanisms of placebo and placebo-related effects across diseases and treatments (Benedetti 2008)

- research has revealed that these psychosocial-induced biochemical changes in a patient’s brain and body in turn may affect the course of a disease and the response to a therapy.

- Full PDF

Placebo mechanisms and reward circuitry: clues from Parkinson’s disease (de la Fuente-Fernández 2004)

- placebo responses are related to the activation of the reward circuitry. Here, the clinical benefit induced by placebos represents the reward.

Podcasts about Placebo

- Brain Science with Ginger Campbell, MD: Neurobiology of Placebos with Fabrizio Benedetti (BSP 77)

- Science VS : Placebo: Can the Mind Cure You?